Guardians of the Galaxy Vol2

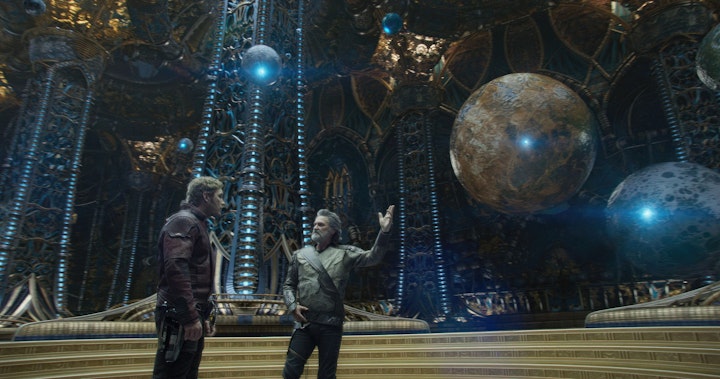

Primarily, we were invited to solve how to represent Ego's backstory as we've been very successful at the exposition moments in previous Marvel films. Chris and James were after a concept that involved a series of 'living paintings' inside Ego's Palace. Secondly, we were asked to design and build Ego's Palace interior out of fractal mathematics as we had some experience working with fractals on AGE OF ULTRON.

The expectations are forever the same: 'Show us something we haven't seen before.'

We looked after most Interior Palace scenes where Ego explains his origins and later reveals his true malevolent purpose. In the Palace Garden scene, Quill learns to summon his 'celestial energy' and play 'celestial catch' with his father. They were compelling scenes with essential plot points to convey – a responsibility we often get when working with Chris.

With a project of this nature, we gathered a small, senior-heavy, generalist team to work through each of the 'unknowns' on the show. The team had Concept, FX, Modelling, Lighting and Comp representatives. At this stage, I like the process to be a little messy, unhindered by the pipeline, with the sole purpose of getting ideas in front of Chris and James as soon as possible.

In this particular film, we had to solve how to 'grow' alien environments, design Quills' Celestial Light', and, as mentioned before, represent Ego's backstory in a visually creative way. As these concepts and solutions coalesced into solutions, they were distributed to the broader department teams, who then further honed the various ideas and managed the turnaround of shots through the Animal Logic production pipeline.

Building the Palace and Garden sets for GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY VOL. 2 presented a unique challenge. The creative brief involved two separate alien environments made from complex mathematical shapes with unprecedented detail.

As an additional challenge, the palace environment had to closely refer to concept art from Marvel's production designer, who based its architectural forms on the intricate fractal work of Hal Tenny. We used a novel approach to modelling fractal objects using point clouds to achieve this challenge. We took advantage of our pipeline's capabilities to integrate FX objects with the environment set pieces and leverage instancing and high levels of geometric complexity using the in-house 'Glimpse' renderer.

Early on, it was clear that the project's creative design process would require a more innovative alternative to a brute force modelling approach. Various techniques for modelling fractals as 3D objects were considered, such as exporting static geometry from external applications, building high-resolution volumes, pre-processing depth and shadow maps, or tracing the fractal function directly at render time. We previously used some of these techniques in AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON and were aware of the limitations.

During the design process, to quickly visualise a variety of potential fractal styles, Matt Ebb, our FX Lead on the show, developed a modular, interactive fractal visualiser within Houdini, which translated fractal formulae to VEX code. Inspired by distance field rendering, the tool used sphere tracing to intersect the fractal surface from the camera efficiently. Rather than rendering pixels, it created a dense point cloud as native Houdini geometry, with data such as normal, colour, occlusion, and other fractal-specific attributes stored per point.

This enabled near real-time 'scouting' through fractal structures in the Houdini viewport, with the advantage of being very easy to freely explore deep inside the fractal space at various scales, opening up a vast range of design possibilities previously not readily available with previous approaches. It soon became apparent that this technique could be used for visualisation and generating final models.

In Modelling, Jonathan Ravagnani led the team in roughing out the basic architecture, making low-resolution bounding objects for 'fractalisation' while also shaping high-resolution framework polygon geometry to be used complementarily with the fractal objects. Fractal point clouds were then generated to fit inside and were sympathetic to the forms of the bounding geometry and delivered in a renderable Glimpse render archive.

Most final objects ranged between 10 to 100 million points. Still, because only externally visible surfaces were evaluated, this allowed for resolving a very high level of detail with a low speed and memory budget. The final generated point clouds could still be manipulated with a high degree of creative control with any of Houdini's standard tools, allowing them to be carved, warped, duplicated and re-arranged after the fact.

Rather than converting to polygon geometry, the fractal point clouds were rendered directly in Glimpse as millions of efficient tightly packed sphere primitives, using the stored fractal normal to override the sphere's shading normal to give the impression of a solid. This was surprisingly effective, even for smooth metallic surfaces, and led to much faster turnarounds than converting to and cleaning up polygon geometry. Using Glimpse's custom ' Ash ' node-based shading system, the surfacing team utilised fractal data stored in the point clouds and other attributes such as density, occlusion, or curvature to control shader parameters.

Instancing the fractal point cloud objects in Glimpse was heavily used to contain memory usage – one of the final sets included 19 fractal set pieces of a total of 646 million points, but would be 3.35 billion if not instanced.

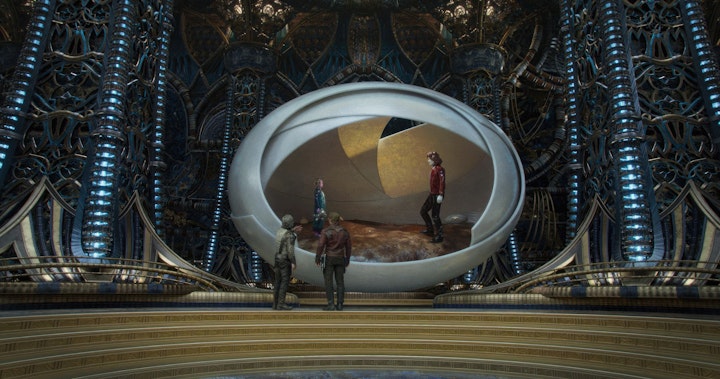

There were several lighting challenges for us on the show. Firstly, the base lighting of Ego's 'virtual' palace set extension had to match the actual lighting of the practical set piece. The filmed set piece was just the central dais with a partial base column in one corner with a bench for the actors to sit on. Chris's onset team had collected plenty of HRDI spheres and colour chart references, so setting up this base lighting was straightforward.

Next, Ian Dodman and his lighting team designed beautiful lighting groups that highlighted the scale and grandeur of the Palace interior. This included lights that raked the delicate filigree and detail on the walls and ceiling, internal lighting on the fractal columns, soft downlighting that illuminated the windows and nooks, and dappled light shafts that highlighted fact and feature lighting for each sculpture. These light groups were rendered separately with many passes, giving the composting team much control to set different moods for each sequence. For example, when we first enter the Palace, the lighting design is late afternoon, warm, inviting and friendly. In contrast, later on, when Ego reveals his true nature, the lighting is intended to be much darker and sinister.

Along with lighting the set, the compositing and rotoscoping teams had a lot of work extracting the actors from the original filmed location and relighting them when they walked past virtual practical light elements or when they interacted with various' energy elements' like the 'Celestial Light ball.'

In the garden, the big challenge for compositing, apart from extracting the actors from the photography, was balancing their lighting between plates shot over different shooting sessions months apart.

Along with extensive balancing of the actors, Quill was cleverly given interactive lighting for his 'Celestial Light' moment. This was achieved by combining comp grading trickery and replacing his hands with CG hands.

Developing the look of Quill's 'celestial light' proved challenging as everyone had a different impression of how we could represent this energy.

Chris's brief was that the energy needed to evoke an electrical quality but be mouldable like bread dough. It needed to feel natural and photographic, be playful like a bubble and reveal that it could be potentially dangerous. We explored the 'celestial light' in the concept department as a series of style frames and motion tests, again using Fractals to help define its exotic look. To integrate the 'celestial energy' with Quill's palms, we needed to build them in 3D and rotomate Quill's performance accurately. Ultimately, we decided to replace his hands entirely with CG's hands, giving us more control.

Various fluid simulations were designed to create plasma arcs, vapour trails, and subdermal lighting of tissue. These FX sims were combined as renderable caches with Quills CG hands, modelled, rigged, and animated in Maya. Our shading team used 'Ash' to handle the texture work, and everything was rendered through 'Glimpse'. Along with combining all these passes, comp applied the usual tricks of relighting the actors, adding lens aberration and glows to the CG to match the original photography.

Some interactive light was in the camera. Most of the relighting of the actors was through carefully tracked and rotoscoped mattes and regrading of the actors in compositing to appear as if they were lit by the 'celestial energy.'

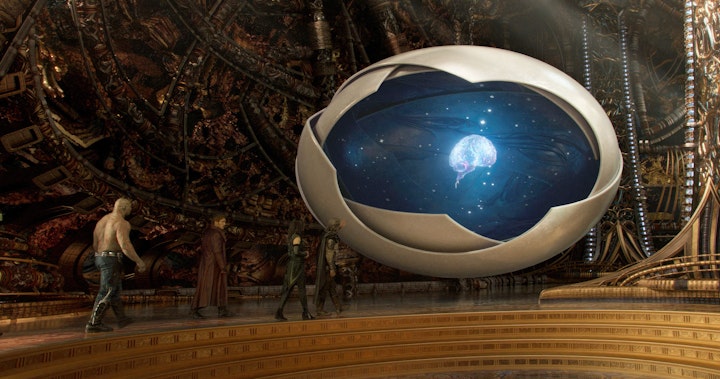

Early on in the pre-production phase of the film, Chris asked us to design and develop a series of 'moving paintings' that depicted Ego's backstory. Chris was keen on pictures formed through falling sand and shared some excellent references. James loved the idea that Ego's backstory was displayed in the manner of the 'Stations of the Cross', which is a classical representation of Jesus's crucifixion.

In Ego's case, the paintings would be several triptychs that depicted his backstory from a lonely intelligence adrift in the cosmos to a 'galactic conqueror.'

One of the other vital factors to consider was that Ego could manipulate and grow anything with his 'celestial energy'. So, the images needed to be beautiful Renaissance paintings that could evolve and change like a picture sequence.

We started the diorama process by exploring how to transform the live-action that James was shooting into shifting sand. These early tests were achieved by tracking the supplied live-action plates and then exporting the motion vectors to Houdini. By using these vectors, we were able to generate particles with the live-action colours attached per pixel. These tests had some promising impressions of falling sand. But while they were impressive, James and Chris were looking for a more hand-drawn, bespoke feel to the paintings.

So Anna Fraser and Sam Ho in the concept team explored many ways of depicting a hand-drawn triptych, from simple pencil sketches to airbrushing to mimicking paint mediums such as gauche and oil paint, while thoroughly examining the sci-fiction artwork of the 70s, especially Chris Foss, Vincent Di Fate and Roger Dean. We even hand-painted over a series of frames from the original film to assess how painful it would be to convert the live-action into a painting. It became evident that any approach we chose needed to be easily split between departments instead of sitting on one artist. We needed a process to turn around each painting relatively quickly as the editorial team would be cutting the live-action up to the last moment. Once a painted style was approved, we would split the task of converting the live action into a moving painting across departments. The rotoscoping team isolated shapes in the live action. The art department animated hand-painted brush strokes that could be applied as part of an oil paint recipe developed in Nuke by Max Stummer. But in the end, after extensive development, it was decided this wasn't the right creative direction for the scene. Marvel felt the moments of Ego's story being depicted in the paintings would have a better impact as 3D animation.

So, it was back to the drawing board. And we threw every talented artist on the team at what the new look would be. Seeing how creative artists from different departments approach the original problem is fun. Within a week, we presented many possible new directions to Chris and the team. Was it made out of dust? Out of light? Do they emanate from the palace columns? Are they made of liquid, gold, or fractals like the Palace?

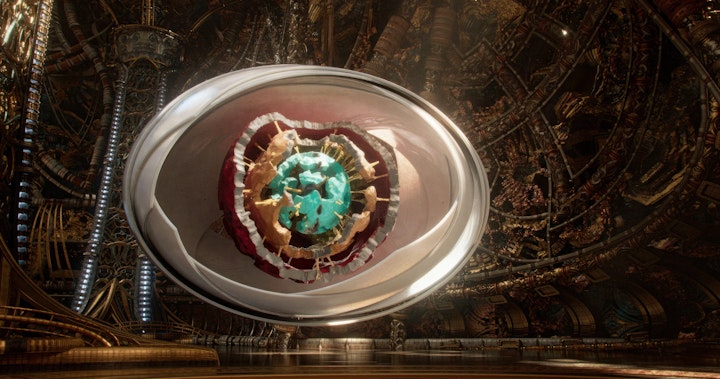

Ultimately, the concept that gave us the most creative options was stylised sculptural forms for the diorama content, framed by an elegantly designed eggshell that mimicked the design of Ego's ship interior. Chris suggested this latter element for us to explore, so we replaced the picture frame idea with the 'eggshell' with layered blades that could be used as wipes to transition between diorama elements. To give the sculptures a realistic finish and scale, we experimented with various shaders from hand-painted stone to brushed-on gold leaf and eventually settled with pearlescent glazes that James likened to Hummel figurines (in a positive way!)

Once we had this new direction, the process became pretty straightforward, and the challenge now was getting it completed in time, as we only had five weeks remaining by this stage. We pre-visualised each diorama's animation, placement, and size to capture the particular 'story beat' and aid the editorial team in locking the scene.

We roto-mated the original live-action for Meredith and Ego's diorama and applied this performance to the stylised sculptural forms. Each diorama also had a hand-painted motif designed by Prema Weir that was 'carved' onto the inside surface of the egg to support the foreground moment.

The dioramas and palace sets were then rendered at 3k and downscaled to 2k as we found the Red Weapon camera resolved so much detail that a standard 2k render looked soft compared to the live action. The renders were then combined with the live action in compositing with all the usual trickery from reflections of the cast on reflective surfaces to the light wrapping of the CG set back onto the actors. In most shots, we completely rotoscoped the actors off the original background and used CG hair wigs to supplement their hair edge detail.

I enjoyed this production. The work was creatively and technically challenging and looked fantastic in the end. But the standout memories were from our camaraderie amongst our internal crew and Chris and his team on the Marvel side. When you are workshopping how to depict the backstory of a giant 'space-brain' who grows his own planet and has impregnated 1000s of alien women, you find you are having some pretty hilarious conversations at times.

Directed by - James Gunn

My Role - VFX Supervisor for Animal Logic

Visual Effects Supervisors - Paul Butterworth, Kirsty Millar, Visual Effects Producer - Jason Bath, Visual Effects Associate Producer - Daniela Giangrande, CG Supervisor - Richard Sutherland, Compositing Supervisor - Alex Lay, Production Coordinators - Sarah Brims, Graham Martin, Lead Digital Artists - Vaughn Arnup, Ian Dodman, Digital Artists - Ali Abdelhak, Rebecca Andrews, Elias Atto, Ryan Basa, Marcus Bain, Alessio Bertotti, Aevar Bjarnason, James Bleakley, Tim Box, Paul Braddock, Alex Coble, Tom Channell, Christian Lik Shan Chu, Lara Collins, Nicholas Cross, Chris Davies, Archie Dowell Anna Fraser, Dominic Femia, Sam Cody Godfrey, Toby Grime, Will Hackett, Mike Holmes, Michael Harkin, Sam Hoh, Josh Hulands, Masha Juergens, Danial Khan, Kieran Lim, Stefan Litterini, Marcin Majewski, Samuel Maniscalco, Jorden Martin, Stephen Midwinter, Norah Mulroney, Daniel Nees, Martin Newcombe, Phinnaeus O’connor, Ean Keat Ong, Paul Perrot, Timea Ng, Matteo Petricone, Shane Rabey, Jonathan Ravagnani, Sebastian Ravagnani, Matt Roe, Craig Rowe, Corin Sadlier, Jacob Santamaria, Richard Skelton, Alex Smith, Max Stummer, Eleanor Sutton, Geeta Thapar, Nori Tominaga, Ryan Trippensee, Ben Walker, Prema Weir, Paul Waggoner, Tom Willekens, Mitchell Woodin, Ben Wotton, Matthew Wynne, Andrew Xu

©2017 Marvel